Share this

Current research into the microbiome of the gut and its relationship to the brain sheds light on the lifestyle-mental health links

Merely a handful of years ago, most of us were told bacteria were bad. We now know we rely of bacteria to stay alive, we are not isolated beings, but symbiotic creatures who co-exist with millions of bacteria who are providing vital functions for us.

It is only recently that we have been able to analyse in detail our gut flora — the reason being that traditional methods of cultivation in gels, simply would not work for many varieties of gut bacteria. With the advent of metagenomics[1], this has changed. We can now study gut flora variety through its DNA as our ability to sequence DNA has improved dramatically. It has opened up a whole new world of research that is beginning to throw valuable light onto the previously little-understood connections between stomach and thinking.

Even more than this, the current research forces us to think of the human ‘entity’ as a symbiotic organism. To put it another way, if all we are is that represented in the human genome, we wouldn’t live very long. Instead, we are utterly dependent on the thousands of species of bacteria that inhabit our gut, skin, mouths and other places! We even have a microbiome ‘cloud’ surrounding us, as demonstrated by a recent study conducted by Meadow[2]. Even in this early stage of research, they were able to detect whether an individual was a man or women in a certain space just from DNA analysis of the ‘cloud’. They were also able to demonstrate that people existing in the same space will cross-colonise their bacterial organisms. It perhaps shows clearly why you should consider who you spend your time with.

To put this in perspective, the human genome represents about 23,000 genes, whereas our microbiome represents over 3,000,000 genes, producing thousands of metabolites (the product of metabolism, with a vast range of different functions) and replacing many of the functions of the host[3]. We are not alone!

So with this unseen world slowly unfolding in research papers, what are the things that we should consider as helping practitioners? First, it is important to remember that a neuroscientist will look at the problem from the perspective of the brain, a gastroenterologist will look at the problem from the perspective of the stomach, a geneticist from the genes etc. As people helping others with life’s challenges, we have to take a holistic overview. When we read about the gut-brain axis, we have to remember that this is a two-way street. What happens in the mind can affect the microbiota of the stomach, and what happens in the stomach can affect the mind.

The mechanism

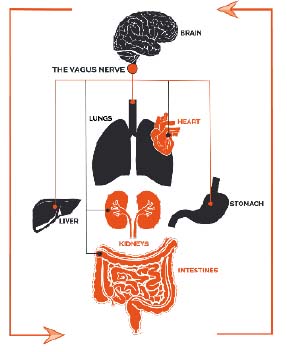

Our gut microbiota communicates with the brain through various mechanisms, which are only recently being discovered. These include hormone signalling, microbial metabolites (such as short-chain fatty acids) and the vagus nerve[4]. Many reading this will perhaps be more familiar with the vagus nerve and its association with diaphragmatic breathing exercises. We know that traditional eastern ‘belly breathing’ has the effect of stimulating the vagus nerve, thereby activating the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e. The rest and digest system), that calms us down and reduces stress and anxiety. The mechanism by which it does this is the production of a substance called acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. When produced it slows heart rate and reduces blood pressure, reverses inflammatory processes and many other positive effects[5]. We now know that this same highway is used by gut microbiota to communicate with our brains, and on its travels, it visits all major organs in the body.

What can we say?

We know that the microbiome is directly linked to obesity and most overweight people show a lower diversity of microbiome than people of a healthy weight. In one experiment reported in the press, Professor Tim Spector had his son eat a diet of McDonald’s for ten days, whilst taking samples of his poo to measure microbiome diversity before, during and after. After three days his energy plummeted, and his friends described him as taking on a grey complexion. What happened internally was that he lost 40% of the variety of his microbiome and after two weeks there was no sign of its recovery[6]. Similarly, antibiotic use has been demonstrated to affect 30% of gut flora, causing significant drops in diversity. It can take years to recover [7].

It is perhaps not novel to suggest that fast food is bad for you but to see how it decimates your internal flora is genuinely alarming. Our gut bacteria produce vital chemical signals to regulate our system and maintain a healthy body and mind. If we kill off a significant amount of it, we are liable to physical and mental repercussions. Already a lower bacterial diversity has been observed in people suffering:

Inflammatory bowel disease

Psoriatic arthritis

Type 1 diabetes

Atopic eczema

Coeliac disease

Obesity

Type 2 diabetes

Arterial stiffness

Crohn’s disease

Other proven disrupters of the gut microbiome are food emulsifiers and artificial sweeteners, which have inflammatory effects in the gut, reduce the effectiveness of the intestinal mucous membrane and have knock-on effects on hunger regulation[3]. There are also many medications, illicit drugs and alcohol that can affect the gut flora.

Microbiome and mental illness

Anxiety and depression.

The specific links are still being studied, but it has been demonstrated in mice: In one experiment, a mouse displaying stress behaviours had a gut contents transplant with a mouse who had no stress behaviours. The result showed a reversal in behaviours, with the stressed mouse becoming calmer and the calm one becoming more stressed[8].

The work of neuroscientist, John Cryan, at the University of Cork, has shown that disruption of the microbiome in mice has caused symptoms that mimic human anxiety, depression and autism. And such symptoms have also been shown to be reversible with probiotic treatment [9]. Cryan said,

“That dietary treatments could be used as either adjunct or sole therapy for mood disorders is not beyond the realm of possibility”.

Which curiously brings us back full circle to the ancient Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, who in 400 BC stated, “Let thy food be thy medicine and thy medicine be thy food.”

Other studies by Nobuyuki Sudo of Kyushu University, have shown that gut microbes can also act to reduce stress responses. Again in mice, he revealed that mice without gut flora showed a significantly higher stress response to confinement than a mouse with healthy gut flora. Further, he showed that this stress response could be treated effectively by introducing a single bacteria — Bifidobacterium infantis. This hints that probiotic treatment could reduce stress responses. Other subsequent studies using the technique of swapping gut bacteria have also shown that behavioural traits follow the contents of the microbiome, including anxiety and mood disorders, as well as physical ailments such as irritable bowel syndrome.

Research in the California Institute of Technology, have also shown fascinating results in relation to autistic traits. Having identified a correlation with mothers who suffered fever during pregnancy and their offspring have a higher chance of being autistic, a non-genetic cause was possible. Inducing the effect in mice, similar ‘autistic traits’ could then be observed in the mice offspring — repetitive behaviour and lessened social interaction and communication. These mice also suffered from leaky intestines, which is important, because as many as 90% of children with autism suffer gastrointestinal symptoms. When the microbiome was studied, the ‘autistic’ mice were shown to have higher levels of Clostridia and Bacteroidia bacterial classes. Whilst it may be different in humans than mice; it provoked the question of whether treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms would also alter autistic symptoms.

By treating these mice with the bacteria, Bacteroides fragilis, they fixed the leaky intestines of the mice and restored more normal microbiota. And importantly the autistic symptoms were reduced [9].

This research is still in its infancy, but researchers across the world are now busy on multiple research projects investigating the nature of this highly complex gut-brain axis. For helping practitioners, it provides another dimension to explore with clients. If anxiety and depression are accompanied by intestinal symptoms (and perhaps even if not), it is certainly worth discussing diet and fermented foods. We certainly know that when recovering from self-destructive states of mind, doing small things to look after the self, are indicative of recovery. In this sense, it is not diet alone or changes of thinking alone that move us to health, but the interplay of both. Healthy thinking can influence healthy lifestyle and diet, and the reverse is also true.

It is humbling to think of ourselves as not merely a single being, but one ‘dominant’ organism, accompanied by millions of smaller organisms. In balance, they work beautifully, but through illness, whether mental or physical, they can fall out of balance. Unhealthy bacteria, fungi and viruses can enter the system, damaging chemicals can be released, just as self-destructive thoughts, beliefs and anxiety can enter the mind and destructive behaviours manifest.

As we work toward health, we slowly ‘weed out’ destructive thoughts, we modify destructive behaviours and challenge false beliefs, perhaps we can also rebalance our internal ecosystems. There is so much more to understand about the gut-brain axis, but we must surely begin to appreciate just how complex we really are. There is a beautiful symmetry between our internal microbiome and our mental/emotional life. Considered mindfully, it should give us pause for thought in what we introduce to our microbiota, just as we should consider what we feed our mind. One does not operate without the other, but through the superhighway that is the vagus nerve, our millions of bacteria communicate via every major organ in the body, to the brain at the end of the line. The Vagus nerve was named after the Latin for ‘wanderer’, a suitable metaphor for all of us on our journey through life.

[If you are interested in finding out more about your own microbiome, there are many ‘gut projects’ worldwide, including the ‘British Gut Project’, britishgut.org/ and the ‘American Gut — Human Food Project, humanfoodproject.com/americangut/ ]

References:

Mochen, A.R., Wieser, W., Tilg, H. (2012). Dietary Factors: Major Regulators of the Gut’s Microbiota. The Korean Society of Gastroenterology. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3493718/

Meadow JF, Altrichter AE, Bateman AC, Stenson J, Brown G, Green JL, Bohannan BJM. (2015) Humans differ in their personal microbial cloud. PeerJ 3:e1258 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1258

Valdes, A.M, Walter, J., Segal, E., Spector, T.D. (June 2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018;361:k2179. Retrieved from: https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k2179

Foster, J.A., Rinaman, L., Cryan, J.F. (Dec 2017). Stress & The gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001

Bergland, C. (Jul 2016). Vagus Nerve Stimulation Dramatically Reduces Inflammation. Psychology Today. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-athletes-way/201607/vagus-nerve-stimulation-dramatically-reduces-inflammation

Spector, T. (May 12 2015). I made my son eat nothing but McDonalds for ten days to prove what fast food does to your gut. Quartz. Retrieved from: https://qz.com/402918/i-made-my-son-eat-nothing-but-mcdonalds-for-ten-days-to-prove-what-fast-food-does-to-your-gut/

Francino, M.P. (12 January 2016). Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Frontiers in Microbiology. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543/full

Kramer, Peter; Bressan, Paola (2015–07–14). “Humans as Superorganisms”. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 10 (4): 464–481.

Schmidt, C (March 1, 2015). Mental Health May Depend on Creatures in the Gut. Scientific American. Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mental-health-may-depend-on-creatures-in-the-gut/