Share this

Lockdown has brought a massive change in routine for almost all of us. Normality for most of us involved; getting up when the alarm goes off, packing the kids off to school, grabbing a coffee on the commute to work, settling into a day's work, punctuated by a cuppa and chat. Heading home at the same time, thinking about what to have for dinner and where the kids should be. There might be time for a spot of TV, catching up with friends on social media or at the pub, reading, a gym class. Everyone is different but you probably had a routine. What that routine does, it removes a cognitive load – you don’t have to think about what you’re doing, it’s what you always do. And as long as you are reasonably happy and secure, you also don’t need to think very much about your life, you don't have to consider life's meaning. And then along comes a pandemic.

The end of the routine, the beginning of a new challenge

Our routines are out the window, apart from a few creative types I know who claim they have been in lockdown for years. With a lot of our activity on hold our mind has idle time. You can fill it with films and TV shows, good books, endless news, but at some point, you’ll have finished the good shows on Netflix and you’re going to start asking yourself some big questions. Perhaps at first, you wonder if things will ever get back to normal. You might then follow up that question with, ‘do I want things to get back to normal?’ And that’s the big one.

Toward a new normal – toward purpose

There has been plenty of discussion in the media about whether we ought to go back to normal at all on a macro level. Certainly many see this as a chance to fix various problems with the way we were doing things. For example, the reduction in air travel provides us with a chance to meet carbon targets. As car noise gives way to bird song we start to consider if we need to make more room for nature. As people become used to meeting digitally, do we need to spend so much time in planes, trains and cars? We might consider the fragility of a global system of money that relies on the impossible notion of endless growth, perhaps there is a new economic model to pursue?

On a personal level, we end up asking equally vital questions. Is the life I was living the one I want? Am I in the right relationship? Why am I doing that soul-destroying job? Everyone treats me like a doormat, why do I let them? Why do I waste my time staring at a screen? Or the question might be more profound, ‘What is the purpose in my life?’

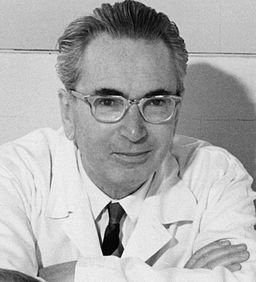

Viktor Frankl’s search for meaning

One man who knew the fundamental importance of purpose, was psychotherapist, Viktor Frankl. Frankl was a student of psychotherapy in Vienna, an acquaintance of Sigmund Freud and an incredible intellect. His family was Jewish and before the outbreak of war, Viktor had the opportunity to go to America to pursue his research. He decided not to go as he thought his ageing parents needed him. One world war and four concentration camps later, Frank emerged, liberated by American troops.

He describes that time after having gained freedom and rushing to discover the whereabouts of his family. He thought he could not have sunk lower than his experience in the nazi camps. Yet discovering he had lost his mother, brother and wife to the gas chambers while his best friend, Hubert Gsur had been beheaded, leaving him alone in Vienna - it was almost unbearable. He had been working to finish a book in the time after camp and the book was to be published,

“But no success can make me happy, everything is weightless, void, vain in my eyes, I feel distant from everything. It all says nothing to me, means nothing… they have left me alone” – Viktor Frankl, 14 September 1945

Finding purpose and the will to go on

Frankl threw himself into his work, at first helping Jewish prisoners recover and then returning to work in Vienna, where he met his second wife. He had already been formulating his psychotherapeutic theories prior to the war and he continued. The experience of the camps served to reinforce his convictions as to what gave humans the will to survive and to thrive. He had witnessed first hand how people of strong physical constitution had withered and died in the camps, while others of seemingly weaker physical attributes had survived. What this latter may have lacked physically, they made up for internally. He saw that survivors had rich internal lives and most importantly – a sense of purpose.

When all possession has gone, you are left with the contents of your mind

When new prisoners arrived in Auschwitz, if they were the ‘lucky’ ones who avoided immediate gassing, they were stripped naked and retained nothing but their belts and spectacles. Even their hair was completely removed. Frankle had had a print-ready manuscript in his possession, that was taken off him and destroyed. This was his most important work up to that point in his life and he knew that he had to complete it when he got the chance. While imprisoned Frankl was separated from his first wife and had no idea if she was alive or dead. Yet he could clearly picture her and had conversations with her in his mind. The love and connection he felt was vital in carrying him through the ordeal. As a doctor, with his psychotherapeutic experience, he was also able to minister to his fellow prisoners, giving him further purpose.

“He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

The father of logotherapy

Frankl emerged from the death camps aged 40 having lost his family and friends. Yet despite this desperate experience, he went on to thrive. He developed his own school of psychotherapeutic treatment — logotherapy. Frankl enjoyed a long and successful career until his death, aged 93 in his hometown of Vienna. He dedicated himself to helping others and his body of work lives on.

In describing logotherapy, Frankl tells the story of someone who asked him to tell him what logotherapy is in one sentence. First Frankl asked him to describe psychotherapy in one sentence and the man said: “During psychoanalysis, the patient must lie down on a couch and tell you things which sometimes are very disagreeable to tell”. To which Frankl extemporised; “In logotherapy, the patient may remain sitting erect but he must hear things which are sometimes very disagreeable to hear”.

Although this was meant as a flippant remark, he argued that there is something to this. Logotherapy comes from the Greek word ‘logos’ which means ‘reason’ or ‘meaning’, and so it can be described as meaning-centred psychotherapy. Whereas other schools of psychoanalysis would concentrate on the negative causes of mental health issues, logotherapy tries to defocus from the vicious circles and feedback mechanisms that feed a state of mental ill-health. In so doing, you begin to breakdown the self-centred mental state of the patient, instead of reinforcing it.

The Existential Vacuum

Now, of course, there are different kinds of mental illnesses, with different causes. Some of what we may now identify as mental health issues (and would previously have been described as neuroses) are not really illnesses at all, but actually a healthy mental reaction to a lack of meaning. Frankl saw that this lack of meaning was widespread and that a condition of the modern age, one that he dubbed, ‘The existential vacuum’.

So what is this state of ‘existential vacuum’? Unlike other animals who do not agonise over their choices, but simply act on instinct, we humans have developed consciousness. Whereas a dog will eat the food in front of them, we can agonise for 30 minutes over what to choose from a menu. We are denied the simplicity of impulse that the dog enjoys, as Frankl says, that avenue, like the garden of Eden, is forever closed to us humans.

What you gain in knowledge, you lose in meaning

As civilisation developed, we developed religious beliefs and traditions that buttressed our mental worlds. However, with the advent of rationalism, we have steadily discarded that tradition and belief. So without instinct and without belief and tradition, we are left in an existential vacuum devoid of meaning. We can put it under a microscope, we can fire neutrons at it, we can develop equations to explain its behaviour. Yet our accumulation of logical, rational explanation does absolutely nothing to fill the void of meaning.

Yet Frankl wasn’t arguing for a return to religious culture, he was remarkably secular in his approach. He believed meaning was to be found not in some great external revelation like St Paul stuck blind on the road to Damascus, but in the experience of each and every one of us. As a man who had witnessed and been a victim of the concentration camps, he could see that his suffering, his burden, could have meaning. He could draw determination to survive from his desire to go on with his work and to see loved ones once again. He argued that unavoidable suffering is indeed something noble and that the sufferer can rightly have pride in it. Conversely, unnecessary suffering is not at all heroic, merely masochistic and should be avoided.

Carry your burden with pride

He once treated a woman who had been desperate to have children. When she did have two sons, one was to die at only 11 years old, while the other was severely disabled and required her constant care. She was driven to such despair, that she even went as far as to attempt suicide with her disabled child. It was her disabled son who dissuaded her. He had meaning in his life and much that he wished to do. Through treatment, his mother was able to change the way that she looked at her situation. Rather than being a victim of terrible and cruel fate, she had been delivered a burden. This was a responsibility that could give her life meaning. When she realised what she could do for her disabled son, she could change her perspective and take pleasure in the burden that she carried.

Meaning for us?

When you finally hit the remote and Netflix contracts into darkness, you have left that smartphone on the kitchen counter and suddenly you find yourself sitting in rare silence. If you give yourself a chance in that silence, then that’s when you start questioning the meaning in your own life. You may be carrying suffering that is unavoidable and if so, you have to try and find your meaning in that suffering. Or it may be that you are choosing to suffer in an act of masochism. In which case it is time to make choices to end that unnecessary suffering.

It could be that you are self-absorbed and telling yourself how cruel life has been to you and how unfair it is. I know I have indulged in this at times. You may be wondering why your loved ones are not doing more to help you. If that is the case then you need to flip it. We can all be guilty of this. We need to look at our suffering with new eyes. Nietsche told us that what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger and it is true.

Take up your burden and see the good in it

If you’re struggling to make sense of your suffering then write about it. The act of writing forces you to order thoughts. When you are forced to put your perceptions on paper you often discover that you have been fooling yourself. Or else you discover that writing is a cathartic process and a way to get your story straight and lay your demons to rest. You can start to recognise what good qualities you have managed to develop as a direct consequence of your suffering, qualities you would rather not sacrifice. And if you choose to leave suffering behind, then you have to look for the courage. With compassion in your heart, you must decide to do what is right for you and for your loved ones, for your community, your country and planet.

Frankl once asked his class of students what they thought his life’s meaning was. After a few moments (to his surprise) a student stood up and responded, ‘it is to help others to find the meaning in their lives’. Your life has meaning and it is right there in your experience. And when you find that meaning, you can not only survive but learn to thrive.

"When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves"

- Viktor Frankl

Reference: